Futures Explained in 200 Lines of Rust

This book aims to explain Futures in Rust using an example driven approach.

The goal is to get a better understanding of Futures by implementing a toy

Reactor, a very simple Executor and our own Futures.

We'll start off a bit differently than most other explanations. Instead of deferring some of the details about what's special about futures in Rust we try to tackle that head on first. We'll be as brief as possible, but as thorough as needed. This way, most question will be answered and explored up front.

We'll end up with futures that can run an any executor like tokio and async_str.

In the end I've made some reader exercises you can do if you want to fix some of the most glaring omissions and shortcuts we took and create a slightly better example yourself.

What does this book give you that isn't covered elsewhere?

That's a valid question. There are many good resources and examples already. First

of all, this book will focus on Futures and async/await specifically and

not in the context of any specific runtime.

Secondly, I've always found small runnable examples very exiting to learn from. Thanks to Mdbook the examples can even be edited and explored further. It's all code that you can download, play with and learn from.

We'll and end up with an understandable example including a Future

implementation, an Executor and a Reactor in less than 200 lines of code.

We don't rely on any dependencies or real I/O which means it's very easy to

explore further and try your own ideas.

Credits and thanks

I'll like to take the chance of thanking the people behind mio, tokio,

async_std, Futures, libc, crossbeam and many other libraries which so

much is built upon. Reading and exploring some of this code is nothing less than

impressive. Even the RFCs that much of the design is built upon is written in a

way that mortal people can understand, and that requires a lot of work. So thanks!

Some background information

Relevant for:

- High level introduction to concurrency in Rust

- Knowing what Rust provides and not when working with async

- Understanding why we need runtimes

- Knowing that Rust has

Futures 1.0andFutures 3.0, and how to deal with them- Getting pointers to further reading on concurrency in general

Before we start implementing our Futures , we'll go through some background

information that will help demystify some of the concepts we encounter.

Actually, after going through these concepts, implementing futures will seem pretty simple. I promise.

Async in Rust

Let's get some of the common roadblocks out of the way first.

Async in Rust is different from most other languages in the sense that Rust has an extremely lightweight runtime.

In languages like C#, JavaScript, Java and GO, the runtime is already there. So if you come from one of those languages this will seem a bit strange to you.

What Rust's standard library takes care of

- The definition of an interruptible task

- An extremely efficient technique to start, suspend, resume and store tasks which are executed concurrently.

- A defined way to wake up a suspended task

That's really what Rusts standard library does. As you see there is no definition of non-blocking I/O, how these tasks are created or how they're run.

What you need to find elsewhere

A runtime. Well, in Rust we normally divide the runtime into two parts:

- The Reactor

- The Executor

Reactors create leaf Futures, and provides things like non-blocking sockets,

an event queue and so on.

Executors, accepts one or more asynchronous tasks called Futures and takes

care of actually running the code we write, suspend the tasks when they're

waiting for I/O and resumes them.

In theory, we could choose one Reactor and one Executor that have nothing

to do with each other besides one creates leaf Futures and one runs them, but

in reality today you'll most often get both in a Runtime.

There are mainly two such runtimes today async_std and tokio.

Quite a bit of complexity attributed to Futures are actually complexity rooted

in runtimes. Creating an efficient runtime is hard. Learning how to use one

correctly can be hard as well, but both are excellent and it's just like

learning any new library.

The difference between Rust and other languages is that you have to make an active choice when it comes to picking a runtime. Most often you'll just use the one provided for you.

Futures 1.0 and Futures 3.0

I'll not spend too much time on this, but it feels wrong to not mention that there have been several iterations on how async should work in Rust.

Futures 3.0 works with the relatively new async/await syntax in Rust and

it's what we'll learn.

Now, since this is rather recent, you can encounter creates that use Futures 1.0

still. This will get resolved in time, but unfortunately it's not always easy

to know in advance.

A good sign is that if you're required to use combinators like and_then then

you're using Futures 1.0.

While not directly compatible, there is a tool that let's you relatively easily

convert a Future 1.0 to a Future 3.0 and vice a verca. You can find all you

need in the futures-rs crate and all information you need here.

First things first

If you find the concepts of concurrency and async programming confusing in

general, I know where you're coming from and I have written some resources to

try to give a high level overview that will make it easier to learn Rusts

Futures afterwards:

- Async Basics - The difference between concurrency and parallelism

- Async Basics - Async history

- Async Basics - Strategies for handling I/O

- Async Basics - Epoll, Kqueue and IOCP

Now learning these concepts by studying futures is making it much harder than it needs to be, so go on and read these chapters. I'll be right here when you're back.

However, if you feel that you have the basics covered, then go right on.

Let's get moving!

Trait objects and fat pointers

Relevant for:

- Understanding how the Waker object is constructed

- Getting a basic feel for "type erased" objects and what they are

- Learning the basics of dynamic dispatch

Trait objects and dynamic dispatch

One of the most confusing topic we encounter when implementing our own Futures

is how we implement a Waker . Creating a Waker involves creating a vtable

which allows us to use dynamic dispatch to call methods on a type erased trait

object we construct our selves.

If you want to know more about dynamic dispatch in Rust I can recommend an article written by Adam Schwalm called Exploring Dynamic Dispatch in Rust.

Let's explain this a bit more in detail.

Fat pointers in Rust

Let's take a look at the size of some different pointer types in Rust. If we run the following code. (You'll have to press "play" to see the output):

# use std::mem::size_of; trait SomeTrait { } fn main() { println!("======== The size of different pointers in Rust: ========"); println!("&dyn Trait:-----{}", size_of::<&dyn SomeTrait>()); println!("&[&dyn Trait]:--{}", size_of::<&[&dyn SomeTrait]>()); println!("Box<Trait>:-----{}", size_of::<Box<SomeTrait>>()); println!("&i32:-----------{}", size_of::<&i32>()); println!("&[i32]:---------{}", size_of::<&[i32]>()); println!("Box<i32>:-------{}", size_of::<Box<i32>>()); println!("&Box<i32>:------{}", size_of::<&Box<i32>>()); println!("[&dyn Trait;4]:-{}", size_of::<[&dyn SomeTrait; 4]>()); println!("[i32;4]:--------{}", size_of::<[i32; 4]>()); }

As you see from the output after running this, the sizes of the references varies. Many are 8 bytes (which is a pointer size on 64 bit systems), but some are 16 bytes.

The 16 byte sized pointers are called "fat pointers" since they carry more extra information.

Example &[i32] :

- The first 8 bytes is the actual pointer to the first element in the array (or part of an array the slice refers to)

- The second 8 bytes is the length of the slice.

Example &dyn SomeTrait:

This is the type of fat pointer we'll concern ourselves about going forward.

&dyn SomeTrait is a reference to a trait, or what Rust calls trait objects.

The layout for a pointer to a trait object looks like this:

- The first 8 bytes points to the

datafor the trait object - The second 8 bytes points to the

vtablefor the trait object

The reason for this is to allow us to refer to an object we know nothing about except that it implements the methods defined by our trait. To allow accomplish this we use dynamic dispatch.

Let's explain this in code instead of words by implementing our own trait object from these parts:

This is an example of editable code. You can change everything in the example and try to run it. If you want to go back, press the undo symbol. Keep an eye out for these as we go forward. Many examples will be editable.

// A reference to a trait object is a fat pointer: (data_ptr, vtable_ptr) trait Test { fn add(&self) -> i32; fn sub(&self) -> i32; fn mul(&self) -> i32; } // This will represent our home brewn fat pointer to a trait object #[repr(C)] struct FatPointer<'a> { /// A reference is a pointer to an instantiated `Data` instance data: &'a mut Data, /// Since we need to pass in literal values like length and alignment it's /// easiest for us to convert pointers to usize-integers instead of the other way around. vtable: *const usize, } // This is the data in our trait object. It's just two numbers we want to operate on. struct Data { a: i32, b: i32, } // ====== function definitions ====== fn add(s: &Data) -> i32 { s.a + s.b } fn sub(s: &Data) -> i32 { s.a - s.b } fn mul(s: &Data) -> i32 { s.a * s.b } fn main() { let mut data = Data {a: 3, b: 2}; // vtable is like special purpose array of pointer-length types with a fixed // format where the three first values has a special meaning like the // length of the array is encoded in the array itself as the second value. let vtable = vec![ 0, // pointer to `Drop` (which we're not implementing here) 6, // lenght of vtable 8, // alignment // we need to make sure we add these in the same order as defined in the Trait. add as usize, // function pointer - try changing the order of `add` sub as usize, // function pointer - and `sub` to see what happens mul as usize, // function pointer ]; let fat_pointer = FatPointer { data: &mut data, vtable: vtable.as_ptr()}; let test = unsafe { std::mem::transmute::<FatPointer, &dyn Test>(fat_pointer) }; // And voalá, it's now a trait object we can call methods on println!("Add: 3 + 2 = {}", test.add()); println!("Sub: 3 - 2 = {}", test.sub()); println!("Mul: 3 * 2 = {}", test.mul()); }

The reason we go through this will be clear later on when we implement our own

Waker we'll actually set up a vtable like we do here to and knowing what

it is will make this much less mysterious.

Generators

Relevant for:

- Understanding how the async/await syntax works since it's how

awaitis implemented- Why we need

Pin- Why Rusts async model is extremely efficient

The motivation for

Generatorscan be found in RFC#2033. It's very well written and I can recommend reading through it (it talks as much about async/await as it does about generators).

The second difficult part that there seems to be a lot of questions about

is Generators and the Pin type. Since they're related we'll start off by

exploring generators first. By doing that we'll soon get to see why

we need to be able to "pin" some data to a fixed location in memory and

get an introduction to Pin as well.

Basically, there were three main options that were discussed when Rust was desiging how the language would handle concurrency:

- Stackful coroutines, better known as green threads.

- Using combinators.

- Stackless coroutines, better known as generators.

Stackful coroutines/green threads

I've written about green threads before. Go check out Green Threads Explained in 200 lines of Rust if you're interested.

Green threads uses the same mechanisms as an OS does by creating a thread for each task, setting up a stack, save the CPU's state and jump from one task(thread) to another by doing a "context switch". We yield control to the scheduler which then continues running a different task.

Rust had green threads once, but they were removed before it hit 1.0. The state

of execution is stored in each stack so in such a solution there would be no need

for async, await, Futures or Pin. All this would be implementation

details for the library.

Combinators

Futures 1.0 used combinators. If you've worked with Promises in JavaScript,

you already know combinators. In Rust they look like this:

let future = Connection::connect(conn_str).and_then(|conn| {

conn.query("somerequest").map(|row|{

SomeStruct::from(row)

}).collect::<Vec<SomeStruct>>()

});

let rows: Result<Vec<SomeStruct>, SomeLibraryError> = block_on(future).unwrap();

While an effective solution there are mainly three downsides I'll focus on:

- The error messages produced could be extremely long and arcane

- Not optimal memory usage

- Did not allow to borrow across combinator steps.

Point #3, is actually a major drawback with Futures 1.0.

Not allowing borrows across suspension points ends up being very un-ergonomic and often requiring extra allocations or copying to accomplish some tasks which is inefficient.

The reason for the higher than optimal memory usage is that this is basically a callback-based approach, where each closure stores all the data it needs for computation. This means that as we chain these, the memory required to store the needed state increases with each added step.

Stackless coroutines/generators

This is the model used in Rust today. It a few notable advantages:

- It's easy to convert normal Rust code to a stackless corotuine using using async/await as keywords (it can even be done using a macro).

- No need for context switching and saving/restoring CPU state

- No need to handle dynamic stack allocation

- Very memory efficient

- Allowed for borrows across suspension points

The last point is in contrast to Futures 1.0. With async/await we can do this:

async fn myfn() {

let text = String::from("Hello world");

let borrowed = &text[0..5];

somefuture.await;

println!("{}", borrowed);

}

Generators are implemented as state machines. The memory footprint of a chain of computations is only defined by the largest footprint any single step requires. That means that adding steps to a chain of computations might not require any added memory at all.

How generators work

In Nightly Rust today you can use the yield keyword. Basically using this

keyword in a closure, converts it to a generator. A closure looking like this

(I'm going to use the terminology that's currently in Rust):

let a = 4;

let b = move || {

println!("Hello");

yield a * 2;

println!("world!");

};

if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = gen.resume() {

println!("Got value {}", n);

}

if let GeneratorState::Complete(()) = gen.resume() {

()

};

Early on, before there was a consensus about the design of Pin, this

compiled to something looking similar to this:

fn main() { let mut gen = GeneratorA::start(4); if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = gen.resume() { println!("Got value {}", n); } if let GeneratorState::Complete(()) = gen.resume() { () }; } // If you've ever wondered why the parameters are called Y and R the naming from // the original rfc most likely holds the answer enum GeneratorState<Y, R> { // originally called `CoResult` Yielded(Y), // originally called `Yield(Y)` Complete(R), // originally called `Return(R)` } trait Generator { type Yield; type Return; fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return>; } enum GeneratorA { Enter(i32), Yield1(i32), Exit, } impl GeneratorA { fn start(a1: i32) -> Self { GeneratorA::Enter(a1) } } impl Generator for GeneratorA { type Yield = i32; type Return = (); fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return> { // lets us get ownership over current state match std::mem::replace(&mut *self, GeneratorA::Exit) { GeneratorA::Enter(a1) => { /*|---code before yield---|*/ /*|*/ println!("Hello"); /*|*/ /*|*/ let a = a1 * 2; /*|*/ /*|------------------------|*/ *self = GeneratorA::Yield1(a); GeneratorState::Yielded(a) } GeneratorA::Yield1(_) => { /*|----code after yield----|*/ /*|*/ println!("world!"); /*|*/ /*|-------------------------|*/ *self = GeneratorA::Exit; GeneratorState::Complete(()) } GeneratorA::Exit => panic!("Can't advance an exited generator!"), } } }

The

yieldkeyword was discussed first in RFC#1823 and in RFC#1832.

Now that you know that the yield keyword in reality rewrites your code to become a state machine,

you'll also know the basics of how await works. It's very similar.

Now, there are some limitations in our naive state machine above. What happens when you have a

borrow across a yield point?

We could forbid that, but one of the major design goals for the async/await syntax has been

to allow this. These kinds of borrows were not possible using Futures 1.0 so we can't let this

limitation just slip and call it a day yet.

Instead of discussing it in theory, let's look at some code.

We'll use the optimized version of the state machines which is used in Rust today. For a more in deapth explanation see Tyler Mandry's execellent article: How Rust optimizes async/await

let a = 4;

let b = move || {

let to_borrow = String::new("Hello");

let borrowed = &to_borrow;

println!("{}", borrowed);

yield a * 2;

println!("{} world!", borrowed);

};

Now what does our rewritten state machine look like with this example?

# #![allow(unused_variables)] #fn main() { # // If you've ever wondered why the parameters are called Y and R the naming from # // the original rfc most likely holds the answer # enum GeneratorState<Y, R> { # // originally called `CoResult` # Yielded(Y), // originally called `Yield(Y)` # Complete(R), // originally called `Return(R)` # } # # trait Generator { # type Yield; # type Return; # fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return>; # } enum GeneratorA { Enter, Yield1 { to_borrow: String, borrowed: &String, // uh, what lifetime should this have? }, Exit, } # impl GeneratorA { # fn start() -> Self { # GeneratorA::Enter # } # } impl Generator for GeneratorA { type Yield = usize; type Return = (); fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return> { // lets us get ownership over current state match std::mem::replace(&mut *self, GeneratorA::Exit) { GeneratorA::Enter => { let to_borrow = String::from("Hello"); let borrowed = &to_borrow; *self = GeneratorA::Yield1 {to_borrow, borrowed}; GeneratorState::Yielded(borrowed.len()) } GeneratorA::Yield1 {to_borrow, borrowed} => { println!("Hello {}", borrowed); *self = GeneratorA::Exit; GeneratorState::Complete(()) } GeneratorA::Exit => panic!("Can't advance an exited generator!"), } } } #}

If you try to compile this you'll get an error (just try it yourself by pressing play).

What is the lifetime of &String. It's not the same as the lifetime of Self. It's not static.

Turns out that it's not possible for us in Rusts syntax to describe this lifetime, which means, that

to make this work, we'll have to let the compiler know that we control this correct.

That means turning to unsafe.

Let's try to write an implementation that will compiler using unsafe. As you'll

see we end up in a self referential struct. A struct which holds references

into itself.

As you'll notice, this compiles just fine!

pub fn main() { let mut gen = GeneratorA::start(); let mut gen2 = GeneratorA::start(); if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = gen.resume() { println!("Got value {}", n); } // If you uncomment this, very bad things can happen. This is why we need `Pin` // std::mem::swap(&mut gen, &mut gen2); if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = gen2.resume() { println!("Got value {}", n); } // if you uncomment `mem::swap`.. this should now start gen2. if let GeneratorState::Complete(()) = gen.resume() { () }; } enum GeneratorState<Y, R> { Yielded(Y), // originally called `Yield(Y)` Complete(R), // originally called `Return(R)` } trait Generator { type Yield; type Return; fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return>; } enum GeneratorA { Enter, Yield1 { to_borrow: String, borrowed: *const String, // Normally you'll see `std::ptr::NonNull` used instead of *ptr }, Exit, } impl GeneratorA { fn start() -> Self { GeneratorA::Enter } } impl Generator for GeneratorA { type Yield = usize; type Return = (); fn resume(&mut self) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return> { // lets us get ownership over current state match self { GeneratorA::Enter => { let to_borrow = String::from("Hello"); let borrowed = &to_borrow; let res = borrowed.len(); // Tricks to actually get a self reference *self = GeneratorA::Yield1 {to_borrow, borrowed: std::ptr::null()}; match self { GeneratorA::Yield1{to_borrow, borrowed} => *borrowed = to_borrow, _ => () }; GeneratorState::Yielded(res) } GeneratorA::Yield1 {borrowed, ..} => { let borrowed: &String = unsafe {&**borrowed}; println!("{} world", borrowed); *self = GeneratorA::Exit; GeneratorState::Complete(()) } GeneratorA::Exit => panic!("Can't advance an exited generator!"), } } }

Try to uncomment the line with

mem::swapand see the result of running this code.

While the example above compiles just fine, we expose users of this code to both possible undefined behavior and other memory errors while using just safe Rust. This is a big problem!

But now, let's prevent the segfault from happening using Pin. We'll discuss

Pin more below, but you'll get an introduction here by just reading the

comments.

#![feature(optin_builtin_traits)] use std::pin::Pin; pub fn main() { let gen1 = GeneratorA::start(); let gen2 = GeneratorA::start(); // Before we pin the pointers, this is safe to do // std::mem::swap(&mut gen, &mut gen2); // constructing a `Pin::new()` on a type which does not implement `Unpin` is unsafe. // However, as I mentioned in the start of the next chapter about `Pin` a // boxed type automatically implements `Unpin` so to stay in safe Rust we can use // that to avoid unsafe. You can also use crates like `pin_utils` to do this safely, // just remember that they use unsafe under the hood so it's like using an already-reviewed // unsafe implementation. let mut pinned1 = Box::pin(gen1); let mut pinned2 = Box::pin(gen2); // Uncomment these if you think it's safe to pin the values to the stack instead // (it is in this case). Remember to comment out the two previous lines first. //let mut pinned1 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut gen1) }; //let mut pinned2 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut gen2) }; if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = pinned1.as_mut().resume() { println!("Got value {}", n); } if let GeneratorState::Yielded(n) = pinned2.as_mut().resume() { println!("Gen2 got value {}", n); }; // This won't work // std::mem::swap(&mut gen, &mut gen2); // This will work but will just swap the pointers. Nothing inherently bad happens here. // std::mem::swap(&mut pinned1, &mut pinned2); let _ = pinned1.as_mut().resume(); let _ = pinned2.as_mut().resume(); } enum GeneratorState<Y, R> { // originally called `CoResult` Yielded(Y), // originally called `Yield(Y)` Complete(R), // originally called `Return(R)` } trait Generator { type Yield; type Return; fn resume(self: Pin<&mut Self>) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return>; } enum GeneratorA { Enter, Yield1 { to_borrow: String, borrowed: *const String, // Normally you'll see `std::ptr::NonNull` used instead of *ptr }, Exit, } impl GeneratorA { fn start() -> Self { GeneratorA::Enter } } // This tells us that the underlying pointer is not safe to move after pinning. In this case, // only we as implementors "feel" this, however, if someone is relying on our Pinned pointer // this will prevent them from moving it. You need to enable the feature flag // `#![feature(optin_builtin_traits)]` and use the nightly compiler to implement `!Unpin`. // Normally, you would use `std::marker::PhantomPinned` to indicate that the // struct is `!Unpin`. impl !Unpin for GeneratorA { } impl Generator for GeneratorA { type Yield = usize; type Return = (); fn resume(self: Pin<&mut Self>) -> GeneratorState<Self::Yield, Self::Return> { // lets us get ownership over current state let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() }; match this { GeneratorA::Enter => { let to_borrow = String::from("Hello"); let borrowed = &to_borrow; let res = borrowed.len(); // Trick to actually get a self reference. We can't reference // the `String` earlier since these references will point to the // location in this stack frame which will not be valid anymore // when this function returns. *this = GeneratorA::Yield1 {to_borrow, borrowed: std::ptr::null()}; match this { GeneratorA::Yield1{to_borrow, borrowed} => *borrowed = to_borrow, _ => () }; GeneratorState::Yielded(res) } GeneratorA::Yield1 {borrowed, ..} => { let borrowed: &String = unsafe {&**borrowed}; println!("{} world", borrowed); *this = GeneratorA::Exit; GeneratorState::Complete(()) } GeneratorA::Exit => panic!("Can't advance an exited generator!"), } } }

Now, as you see, the user of this code must either:

- Box the value and thereby allocating it on the heap

- Use

unsafeand pin the value to the stack. The user knows that if they move the value afterwards it will violate the guarantee they promise to uphold when they did their unsafe implementation.

Now, the code which is created and the need for Pin to allow for borrowing

across yield points should be pretty clear.

Pin

Relevant for

- To understand

GeneratorsandFutures- Knowing how to use

Pinis required when implementing your ownFuture- To understand self-referential types in Rust

- This is the way borrowing across

awaitpoints is accomplished

Pinwas suggested in RFC#2349

We already got a brief introduction of Pin in the previous chapters, so we'll

start off here with some definitions and a set of rules to remember.

Definitions

Pin consists of the Pin type and the Unpin marker. Pin's purpose in life is

to govern the rules that need to apply for types which implement !Unpin.

Pin is only relevant for pointers. A reference to an object is a pointer.

Yep, that's double negation for you, as in "does-not-implement-unpin". For this chapter and only this chapter we'll rename these markers to:

!Unpin=MustStayandUnpin=CanMove

It just makes it so much easier to understand them.

Rules to remember

-

If

T: CanMove(which is the default), thenPin<'a, T>is entirely equivalent to&'a mut T. in other words:CanMovemeans it's OK for this type to be moved even when pinned, soPinwill have no effect on such a type. -

Getting a

&mut Tto a pinned pointer requires unsafe ifT: MustStay. In other words: requiring a pinned pointer to a type which isMustStayprevents the user of that API from moving that value unless it choses to writeunsafecode. -

Pinning does nothing special with that memory like putting it into some "read only" memory or anything fancy. It only tells the compiler that some operations on this value should be forbidden.

-

Most standard library types implement

CanMove. The same goes for most "normal" types you encounter in Rust.FuturesandGeneratorsare two exceptions. -

The main use case for

Pinis to allow self referential types, the whole justification for stabilizing them was to allow that. There are still corner cases in the API which are being explored. -

The implementation behind objects that are

MustStayis most likely unsafe. Moving such a type can cause the universe to crash. As of the time of writing this book, creating an reading fields of a self referential struct still requiresunsafe. -

You're not really meant to be implementing

MustStay, but you can on nightly with a feature flag, or by addingstd::marker::PhantomPinnedto your type. -

When Pinning, you can either pin a value to memory either on the stack or on the heap.

-

Pinning a

MustStaypointer to the stack requiresunsafe -

Pinning a

MustStaypointer to the heap does not requireunsafe. There is a shortcut for doing this usingBox::pin.

Unsafe code does not mean it's literally "unsafe", it only relieves the guarantees you normally get from the compiler. An

unsafeimplementation can be perfectly safe to do, but you have no safety net.

Let's take a look at an example:

use std::pin::Pin; fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); test1.init(); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); test2.init(); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); // try commenting out this line println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); } #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { let a = String::from(txt); Test { a, b: std::ptr::null(), } } fn init(&mut self) { let self_ref: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ref; } fn a(&self) -> &str { &self.a } fn b(&self) -> &String { unsafe {&*(self.b)} } }

Let's walk through this example since we'll be using it the rest of this chapter.

We have a self-referential struct Test. Test needs an init method to be

created which is strange but we'll need that to keep this example as short as

possible.

Test provides two methods to get a reference to the value of the fields

a and b. Since b is a reference to a we store it as a pointer since

the borrowing rules of Rust doesn't allow us to define this lifetime.

In our main method we first instantiate two instances of Test and print out

the value of the fields on test1. We get:

a: test1, b: test1

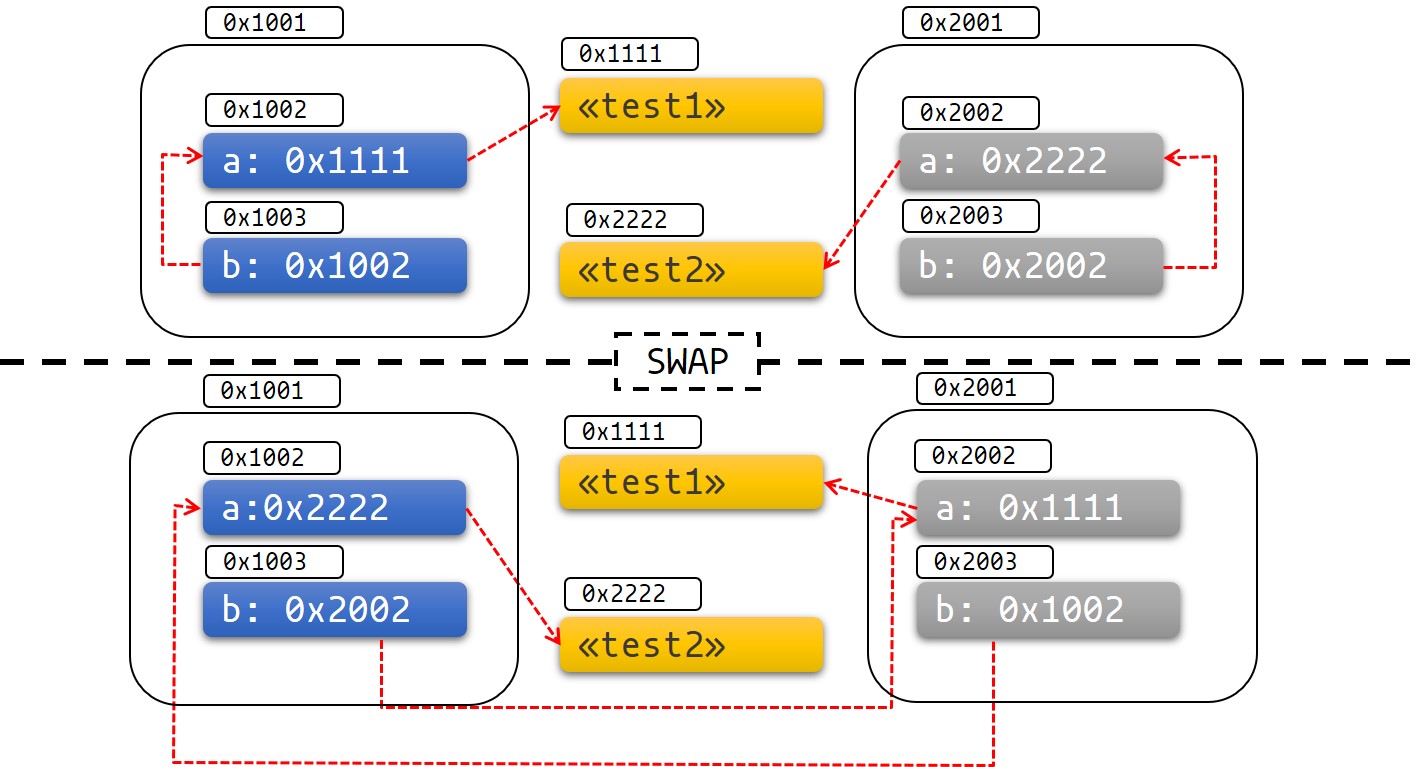

Next we swap the data stored at the memory location which test1 is pointing to

with the data stored at the memory location test2 is pointing to and vice a verca.

We should expect that printing the fields of test2 should display the same as

test1 (since the object we printed before the swap has moved there now).

a: test1, b: test2

The pointer to b still points to the old location. That location is now

occupied with the string "test2". This can be a bit hard to visualize so I made

a figure that i hope can help.

Fig 1: Before and after swap

As you can see this results in unwanted behavior. It's easy to get this to segfault, show UB and fail in other spectacular ways as well.

If we change the example to using Pin instead:

use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { let a = String::from(txt); Test { a, b: std::ptr::null(), // This makes our type `!Unpin` _marker: PhantomPinned, } } fn init(&mut self) { let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ptr; } fn a<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a String { unsafe { &*(self.b) } } } pub fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); test1.init(); let mut test1_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) }; let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); test2.init(); let mut test2_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) }; println!( "a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test1_pin.as_ref()), Test::b(test1_pin.as_ref()) ); // Try to uncomment this and see what happens // std::mem::swap(test1_pin.as_mut(), test2_pin.as_mut()); println!( "a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test2_pin.as_ref()), Test::b(test2_pin.as_ref()) ); }

Now, what we've done here is pinning a stack address. That will always be

unsafe if our type implements !Unpin (aka MustStay).

We use some tricks here, including requiring an init. If we want to fix that

and let users avoid unsafe we need to pin our data on the heap instead.

Stack pinning will always depend on the current stack frame we're in, so we can't create a self referential object in one stack frame and return it since any pointers we take to "self" is invalidated.

The next example solves some of our friction at the cost of a heap allocation.

use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Pin<Box<Self>> { let a = String::from(txt); let t = Test { a, b: std::ptr::null(), _marker: PhantomPinned, }; let mut boxed = Box::pin(t); let self_ptr: *const String = &boxed.as_ref().a; unsafe { boxed.as_mut().get_unchecked_mut().b = self_ptr }; boxed } fn a<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a String { unsafe { &*(self.b) } } } pub fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); println!("a: {}, b: {}",test1.as_ref().a(), test1.as_ref().b()); // Try to uncomment this and see what happens // std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); println!("a: {}, b: {}",test2.as_ref().a(), test2.as_ref().b()); }

The fact that boxing (heap allocating) a value that implements !Unpin is safe

makes sense. Once the data is allocated on the heap it will have a stable address.

There is no need for us as users of the API to take special care and ensure that the self-referential pointer stays valid.

There are ways to safely give some guarantees on stack pinning as well, but right now you need to use a crate like pin_utils:pin_utils to do that.

Projection/structural pinning

In short, projection is using a field on your type. mystruct.field1 is a

projection. Structural pinning is using Pin on struct fields. This has several

caveats and is not something you'll normally see so I refer to the documentation

for that.

Pin and Drop

The Pin guarantee exists from the moment the value is pinned until it's dropped.

In the Drop implementation you take a mutable reference to self, which means

extra care must be taken when implementing Drop for pinned types.

Putting it all together

This is exactly what we'll do when we implement our own Futures stay tuned,

we're soon finished.

Reactor/Executor Pattern

Relevant for:

- Getting a high level overview of a common runtime model in Rust

- Introducing these terms so we're on the same page when referring to them

- Getting pointers on where to get more information about this pattern

If you don't know what this is, you should take a few minutes and read about

it. You will encounter the term Reactor and Executor a lot when working

with async code in Rust.

I have written a quick introduction explaining this pattern before which you can take a look at here:

I'll re-iterate the most important parts here.

This pattern consists of at least 2 parts:

- A reactor

- handles some kind of event queue

- has the responsibility of respoonding to events

- An executor

- Often has a scheduler

- Holds a set of suspended tasks, and has the responsibility of resuming them when an event has occurred

- The concept of a task

- A set of operations that can be stopped half way and resumed later on

This kind of pattern common outside of Rust as well, but it's especially popular in Rust due to how well it alignes with the API provided by Rusts standard library. This model separates concerns between handling and scheduling tasks, and queing and responding to I/O events.

The Reactor

Since concurrency mostly makes sense when interacting with the outside world (or at least some peripheral), we need something to actually abstract over this interaction in an asynchronous way.

This is the Reactors job. Most often you'll

see reactors in rust use a library called Mio, which provides non

blocking APIs and event notification for several platforms.

The reactor will typically give you something like a TcpStream (or any other resource) which you'll use to create an I/O request. What you get in return

is a Future.

We can call this kind of Future a "leaf Future`, since it's some operation

we'll actually wait on and that we can chain operations on which are performed

once the leaf future is ready.

The Task

In Rust we call an interruptible task a Future. Futures has a well defined interface, which means they can be used across the entire ecosystem. We can chain

these Futures so that once a "leaf future" is ready we'll perform a set of

operations.

These operations can spawn new leaf futures themselves.

The executor

The executors task is to take one or more futures and run them to completion.

The first thing an executor does when it get's a Future is polling it.

When polled one of three things can happen:

- The future returns

Readyand we schedule whatever chained operations to run - The future hasn't been polled before so we pass it a

Wakerand suspend it - The futures has been polled before but is not ready and returns

Pending

Rust provides a way for the Reactor and Executor to communicate through the Waker. The reactor stores this Waker and calls Waker::wake() on it once

a Future has resolved and should be polled again.

We'll get to know these concepts better in the following chapters.

Providing these pieces let's Rust take care a lot of the ergonomic "friction" programmers meet when faced with async code, and still not dictate any preferred runtime to actually do the scheduling and I/O queues.

With that out of the way, let's move on to actually implement all this in our example.

Futures in Rust

We'll create our own Futures together with a fake reactor and a simple

executor which allows you to edit, run an play around with the code right here

in your browser.

I'll walk you through the example, but if you want to check it out closer, you

can always clone the repository and play around with the code yourself. There

are two branches. The basic_example is this code, and the basic_example_commented

is this example with extensive comments.

Implementing our own Futures

Let's start with why we wrote this book, by implementing our own Futures.

use std::{ future::Future, pin::Pin, sync::{mpsc::{channel, Sender}, Arc, Mutex}, task::{Context, Poll, RawWaker, RawWakerVTable, Waker}, thread::{self, JoinHandle}, time::{Duration, Instant} }; fn main() { // This is just to make it easier for us to see when our Future was resolved let start = Instant::now(); // Many runtimes create a glocal `reactor` we pass it as an argument let reactor = Reactor::new(); // Since we'll share this between threads we wrap it in a // atmically-refcounted- mutex. let reactor = Arc::new(Mutex::new(reactor)); // We create two tasks: // - first parameter is the `reactor` // - the second is a timeout in seconds // - the third is an `id` to identify the task let future1 = Task::new(reactor.clone(), 2, 1); let future2 = Task::new(reactor.clone(), 1, 2); // an `async` block works the same way as an `async fn` in that it compiles // our code into a state machine, `yielding` at every `await` point. let fut1 = async { let val = future1.await; let dur = (Instant::now() - start).as_secs_f32(); println!("Future got {} at time: {:.2}.", val, dur); }; let fut2 = async { let val = future2.await; let dur = (Instant::now() - start).as_secs_f32(); println!("Future got {} at time: {:.2}.", val, dur); }; // Our executor can only run one and one future, this is pretty normal // though. You have a set of operations containing many futures that // ends up as a single future that drives them all to completion. let mainfut = async { fut1.await; fut2.await; }; // This executor will block the main thread until the futures is resolved block_on(mainfut); // When we're done, we want to shut down our reactor thread so our program // ends nicely. reactor.lock().map(|mut r| r.close()).unwrap(); } //// ============================ EXECUTOR ==================================== // Our executor takes any object which implements the `Future` trait fn block_on<F: Future>(mut future: F) -> F::Output { // the first thing we do is to construct a `Waker` which we'll pass on to // the `reactor` so it can wake us up when an event is ready. let mywaker = Arc::new(MyWaker{ thread: thread::current() }); let waker = waker_into_waker(Arc::into_raw(mywaker)); // The context struct is just a wrapper for a `Waker` object. Maybe in the // future this will do more, but right now it's just a wrapper. let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&waker); // We poll in a loop, but it's not a busy loop. It will only run when // an event occurs, or a thread has a "spurious wakeup" (an unexpected wakeup // that can happen for no good reason). let val = loop { // So, since we run this on one thread and run one future to completion // we can pin the `Future` to the stack. This is unsafe, but saves an // allocation. We could `Box::pin` it too if we wanted. This is however // safe since we don't move the `Future` here. let pinned = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut future) }; match Future::poll(pinned, &mut cx) { // when the Future is ready we're finished Poll::Ready(val) => break val, // If we get a `pending` future we just go to sleep... Poll::Pending => thread::park(), }; }; val } // ====================== FUTURE IMPLEMENTATION ============================== // This is the definition of our `Waker`. We use a regular thread-handle here. // It works but it's not a good solution. If one of our `Futures` holds a handle // to our thread and takes it with it to a different thread the followinc could // happen: // 1. Our future calls `unpark` from a different thread // 2. Our `executor` thinks that data is ready and wakes up and polls the future // 3. The future is not ready yet but one nanosecond later the `Reactor` gets // an event and calles `wake()` which also unparks our thread. // 4. This could all happen before we go to sleep again since these processes // run in parallel. // 5. Our reactor has called `wake` but our thread is still sleeping since it was // awake alredy at that point. // 6. We're deadlocked and our program stops working // There are many better soloutions, here are some: // - Use `std::sync::CondVar` // - Use [crossbeam::sync::Parker](https://docs.rs/crossbeam/0.7.3/crossbeam/sync/struct.Parker.html) #[derive(Clone)] struct MyWaker { thread: thread::Thread, } // This is the definition of our `Future`. It keeps all the information we // need. This one holds a reference to our `reactor`, that's just to make // this example as easy as possible. It doesn't need to hold a reference to // the whole reactor, but it needs to be able to register itself with the // reactor. #[derive(Clone)] pub struct Task { id: usize, reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>, data: u64, is_registered: bool, } // These are function definitions we'll use for our waker. Remember the // "Trait Objects" chapter from the book. fn mywaker_wake(s: &MyWaker) { let waker_ptr: *const MyWaker = s; let waker_arc = unsafe {Arc::from_raw(waker_ptr)}; waker_arc.thread.unpark(); } // Since we use an `Arc` cloning is just increasing the refcount on the smart // pointer. fn mywaker_clone(s: &MyWaker) -> RawWaker { let arc = unsafe { Arc::from_raw(s).clone() }; std::mem::forget(arc.clone()); // increase ref count RawWaker::new(Arc::into_raw(arc) as *const (), &VTABLE) } // This is actually a "helper funtcion" to create a `Waker` vtable. In contrast // to when we created a `Trait Object` from scratch we don't need to concern // ourselves with the actual layout of the `vtable` and only provide a fixed // set of functions const VTABLE: RawWakerVTable = unsafe { RawWakerVTable::new( |s| mywaker_clone(&*(s as *const MyWaker)), // clone |s| mywaker_wake(&*(s as *const MyWaker)), // wake |s| mywaker_wake(*(s as *const &MyWaker)), // wake by ref |s| drop(Arc::from_raw(s as *const MyWaker)), // decrease refcount ) }; // Instead of implementing this on the `MyWaker` oject in `impl Mywaker...` we // just use this pattern instead since it saves us some lines of code. fn waker_into_waker(s: *const MyWaker) -> Waker { let raw_waker = RawWaker::new(s as *const (), &VTABLE); unsafe { Waker::from_raw(raw_waker) } } impl Task { fn new(reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>, data: u64, id: usize) -> Self { Task { id, reactor, data, is_registered: false, } } } // This is our `Future` implementation impl Future for Task { // The output for this kind of `leaf future` is just an `usize`. For other // futures this could be something more interesting like a byte stream. type Output = usize; fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let mut r = self.reactor.lock().unwrap(); // we check with the `Reactor` if this future is in its "readylist" if r.is_ready(self.id) { // if it is, we return the data. In this case it's just the ID of // the task. Poll::Ready(self.id) } else if self.is_registered { // If the future is registered alredy, we just return `Pending` Poll::Pending } else { // If we get here, it must be the first time this `Future` is polled // so we register a task with our `reactor` r.register(self.data, cx.waker().clone(), self.id); // oh, we have to drop the lock on our `Mutex` here because we can't // have a shared and exclusive borrow at the same time drop(r); self.is_registered = true; Poll::Pending } } } // =============================== REACTOR =================================== // This is a "fake" reactor. It does no real I/O, but that also makes our // code possible to run in the book and in the playground struct Reactor { // we need some way of registering a Task with the reactor. Normally this // would be an "interest" in an I/O event dispatcher: Sender<Event>, handle: Option<JoinHandle<()>>, // This is a list of tasks that are ready, which means they should be polled // for data. readylist: Arc<Mutex<Vec<usize>>>, } // We just have two kind of events. A timeout event, a "timeout" event called // `Simple` and a `Close` event to close down our reactor. #[derive(Debug)] enum Event { Close, Simple(Waker, u64, usize), } impl Reactor { fn new() -> Self { // The way we register new events with our reactor is using a regular // channel let (tx, rx) = channel::<Event>(); let readylist = Arc::new(Mutex::new(vec![])); let rl_clone = readylist.clone(); // This `Vec` will hold handles to all threads we spawn so we can // join them later on and finish our programm in a good manner let mut handles = vec![]; // This will be the "Reactor thread" let handle = thread::spawn(move || { // This simulates some I/O resource for event in rx { let rl_clone = rl_clone.clone(); match event { // If we get a close event we break out of the loop we're in Event::Close => break, Event::Simple(waker, duration, id) => { // When we get an event we simply spawn a new thread... let event_handle = thread::spawn(move || { //... which will just sleep for the number of seconds // we provided when creating the `Task`. thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(duration)); // When it's done sleeping we put the ID of this task // on the "readylist" rl_clone.lock().map(|mut rl| rl.push(id)).unwrap(); // Then we call `wake` which will wake up our // executor and start polling the futures waker.wake(); }); handles.push(event_handle); } } } // When we exit the Reactor we first join all the handles on // the child threads we've spawned so we catch any panics and // release all resources. for handle in handles { handle.join().unwrap(); } }); Reactor { readylist, dispatcher: tx, handle: Some(handle), } } fn register(&mut self, duration: u64, waker: Waker, data: usize) { // registering an event is as simple as sending an `Event` through // the channel. self.dispatcher .send(Event::Simple(waker, duration, data)) .unwrap(); } fn close(&mut self) { self.dispatcher.send(Event::Close).unwrap(); } // We need a way to check if any event's are ready. This will simply // look through the "readylist" for an event macthing the ID we want to // check for. fn is_ready(&self, id_to_check: usize) -> bool { self.readylist .lock() .map(|rl| rl.iter().any(|id| *id == id_to_check)) .unwrap() } } // When our `Reactor` is dropped we join the reactor thread with the thread // owning our `Reactor` so we catch any panics and release all resources. // It's not needed for this to work, but it really is a best practice to join // all threads you spawn. impl Drop for Reactor { fn drop(&mut self) { self.handle.take().map(|h| h.join().unwrap()).unwrap(); } }

Our finished code

Here is the whole example. You can edit it right here in your browser and run it yourself. Have fun!

use std::{ future::Future, pin::Pin, sync::{mpsc::{channel, Sender}, Arc, Mutex}, task::{Context, Poll, RawWaker, RawWakerVTable, Waker}, thread::{self, JoinHandle}, time::{Duration, Instant} }; fn main() { let start = Instant::now(); // Many runtimes create a glocal `reactor` we pass it as an argument let reactor = Reactor::new(); let reactor = Arc::new(Mutex::new(reactor)); let future1 = Task::new(reactor.clone(), 2, 1); let future2 = Task::new(reactor.clone(), 1, 2); let fut1 = async { let val = future1.await; let dur = (Instant::now() - start).as_secs_f32(); println!("Future got {} at time: {:.2}.", val, dur); }; let fut2 = async { let val = future2.await; let dur = (Instant::now() - start).as_secs_f32(); println!("Future got {} at time: {:.2}.", val, dur); }; let mainfut = async { fut1.await; fut2.await; }; block_on(mainfut); reactor.lock().map(|mut r| r.close()).unwrap(); } //// ============================ EXECUTOR ==================================== fn block_on<F: Future>(mut future: F) -> F::Output { let mywaker = Arc::new(MyWaker{ thread: thread::current() }); let waker = waker_into_waker(Arc::into_raw(mywaker)); let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&waker); let val = loop { let pinned = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut future) }; match Future::poll(pinned, &mut cx) { Poll::Ready(val) => break val, Poll::Pending => thread::park(), }; }; val } // ====================== FUTURE IMPLEMENTATION ============================== #[derive(Clone)] struct MyWaker { thread: thread::Thread, } #[derive(Clone)] pub struct Task { id: usize, reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>, data: u64, is_registered: bool, } fn mywaker_wake(s: &MyWaker) { let waker_ptr: *const MyWaker = s; let waker_arc = unsafe {Arc::from_raw(waker_ptr)}; waker_arc.thread.unpark(); } fn mywaker_clone(s: &MyWaker) -> RawWaker { let arc = unsafe { Arc::from_raw(s).clone() }; std::mem::forget(arc.clone()); // increase ref count RawWaker::new(Arc::into_raw(arc) as *const (), &VTABLE) } const VTABLE: RawWakerVTable = unsafe { RawWakerVTable::new( |s| mywaker_clone(&*(s as *const MyWaker)), // clone |s| mywaker_wake(&*(s as *const MyWaker)), // wake |s| mywaker_wake(*(s as *const &MyWaker)), // wake by ref |s| drop(Arc::from_raw(s as *const MyWaker)), // decrease refcount ) }; fn waker_into_waker(s: *const MyWaker) -> Waker { let raw_waker = RawWaker::new(s as *const (), &VTABLE); unsafe { Waker::from_raw(raw_waker) } } impl Task { fn new(reactor: Arc<Mutex<Reactor>>, data: u64, id: usize) -> Self { Task { id, reactor, data, is_registered: false, } } } impl Future for Task { type Output = usize; fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let mut r = self.reactor.lock().unwrap(); if r.is_ready(self.id) { Poll::Ready(self.id) } else if self.is_registered { Poll::Pending } else { r.register(self.data, cx.waker().clone(), self.id); drop(r); self.is_registered = true; Poll::Pending } } } // =============================== REACTOR =================================== struct Reactor { dispatcher: Sender<Event>, handle: Option<JoinHandle<()>>, readylist: Arc<Mutex<Vec<usize>>>, } #[derive(Debug)] enum Event { Close, Simple(Waker, u64, usize), } impl Reactor { fn new() -> Self { let (tx, rx) = channel::<Event>(); let readylist = Arc::new(Mutex::new(vec![])); let rl_clone = readylist.clone(); let mut handles = vec![]; let handle = thread::spawn(move || { // This simulates some I/O resource for event in rx { let rl_clone = rl_clone.clone(); match event { Event::Close => break, Event::Simple(waker, duration, id) => { let event_handle = thread::spawn(move || { thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(duration)); rl_clone.lock().map(|mut rl| rl.push(id)).unwrap(); waker.wake(); }); handles.push(event_handle); } } } for handle in handles { handle.join().unwrap(); } }); Reactor { readylist, dispatcher: tx, handle: Some(handle), } } fn register(&mut self, duration: u64, waker: Waker, data: usize) { self.dispatcher .send(Event::Simple(waker, duration, data)) .unwrap(); } fn close(&mut self) { self.dispatcher.send(Event::Close).unwrap(); } fn is_ready(&self, id_to_check: usize) -> bool { self.readylist .lock() .map(|rl| rl.iter().any(|id| *id == id_to_check)) .unwrap() } } impl Drop for Reactor { fn drop(&mut self) { self.handle.take().map(|h| h.join().unwrap()).unwrap(); } }

Conclusion and exercises

Reader excercises

So our implementation has taken some obvious shortcuts and could use some improvement. Actually digging into the code and try things yourself is a good way to learn. Here are som relatively simple and good exercises:

Avoid thread::park

The big problem using Thread::park and Thread::unpark is that the user can access these same methods from their own code. Try to use another method of telling the OS to suspend our thread and wake it up again on our command. Some hints:

- Check out

CondVars, here are two sources Wikipedia and the docs forCondVar - Take a look at crates that help you with this exact problem like Crossbeam (specifically the

Parker)

Avoid wrapping the whole Reactor in a mutex and pass it around

First of all, protecting the whole Reactor and passing it around is overkill. We're only interested in synchronizing some parts of the information it contains. Try to refactor that out and only synchronize access to what's really needed.

- Do you want to pass around a reference to this information using an

Arc? - Do you want to make this information global so it can be accessed from anywhere?

Next , using a Mutex as a synchronization mechanism might be overkill since many methods only reads data.

- Could an

RwLockbe more efficient some places? - Could you use any of the synchronization mechanisms in Crossbeam?

- Do you want to dig into atomics in Rust and implement a synchronization mechanism of your own?

Avoid creating a new Waker for every event

Right now we create a new instance of a Waker for every event we create. Is this really needed?

- Could we create one instance and then cache it (see this article from

u/sjepang)?- Should we cache it in

thread_local!storage? - Or should be cache it using a global constant?

- Should we cache it in

Could we implement more methods on our executor?

What about CPU intensive tasks? Right now they'll prevent our executor thread from progressing an handling events. Could you create a thread pool and create a method to send such tasks to the thread pool instead together with a Waker which will wake up the executor thread once the CPU intensive task is done?

In both async_std and tokio this method is called spawn_blocking, a good place to start is to read the documentation and the code thy use to implement that.

Further reading

There are many great resources for further study. Here are some of my suggestions:

The Asyc book: