10 KiB

Pin

Relevant for

- Understanding

GeneratorsandFutures- Knowing how to use

Pinis required when implementing your ownFuture- Understanding how to make self-referential types safe to use in Rust

- Learning how borrowing across

awaitpoints is accomplished

Pinwas suggested in RFC#2349

We already got a brief introduction of Pin in the previous chapters, so we'll

start off without any further introduction.

Let's jump strait to some definitions and then create a set of rules to remember. Let's call them the 10 commandments of Pinning. Unfortunately, my stonemasonry skills are rather poor, so we'll have to settle by writing them in markdown (for now).

Definitions

Pin consists of the Pin type and the Unpin marker. Pin's purpose in life is

to govern the rules that need to apply for types which implement !Unpin.

Pin is only relevant for pointers. A reference to an object is a pointer.

Yep, you're right, that's double negation right there. !Unpin means

"not-un-pin".

This naming scheme is Rust deliberately testing if you're too tired to safely implement a type with this marker. If you're starting to get confused by

!Unpin it's a good sign that it's time to lay down the work and start over

tomorrow with a fresh mind.

That was of course a joke. There are very valid reasons for the names that were chosen. If you want you can read a bit of the discussion from the internals thread. The best takeaway from there in my eyes is this quote from

tmandry:Think of taking a thumbtack out of a cork board so you can tweak how a flyer looks. For Unpin types, this unpinning is directly supported by the type; you can do this implicitly. You can even swap out the object with another before you put the pin back. For other types, you must be much more careful.

For the next paragraph we'll rename these markers to:

!Unpin=MustStayandUnpin=CanMove

It just makes it much easier to talk about them.

Rules to remember

-

If

T: CanMove(which is the default), thenPin<'a, T>is entirely equivalent to&'a mut T. in other words:CanMovemeans it's OK for this type to be moved even when pinned, soPinwill have no effect on such a type. -

Getting a

&mut Tto a pinned pointer requires unsafe ifT: MustStay. In other words: requiring a pinned pointer to a type which isMustStayprevents the user of that API from moving that value unless it choses to writeunsafecode. -

Pinning does nothing special with memory allocation like putting it into some "read only" memory or anything fancy. It only tells the compiler that some operations on this value should be forbidden.

-

Most standard library types implement

CanMove. The same goes for most "normal" types you encounter in Rust.FuturesandGeneratorsare two exceptions. -

The main use case for

Pinis to allow self referential types, the whole justification for stabilizing them was to allow that. There are still corner cases in the API which are being explored. -

The implementation behind objects that are

MustStayis most likely unsafe. Moving such a type can cause the universe to crash. As of the time of writing this book, creating and reading fields of a self referential struct still requiresunsafe. -

You can add a

MustStaybound on a type on nightly with a feature flag, or by addingstd::marker::PhantomPinnedto your type on stable. -

You can either pin a value to memory on the stack or on the heap.

-

Pinning a

MustStaypointer to the stack requiresunsafe -

Pinning a

MustStaypointer to the heap does not requireunsafe. There is a shortcut for doing this usingBox::pin.

Unsafe code does not mean it's literally "unsafe", it only relieves the guarantees you normally get from the compiler. An

unsafeimplementation can be perfectly safe to do, but you have no safety net.

Let's take a look at an example:

use std::pin::Pin;

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b());

std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); // try commenting out this line

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b());

}

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

let a = String::from(txt);

Test {

a,

b: std::ptr::null(),

}

}

fn init(&mut self) {

let self_ref: *const String = &self.a;

self.b = self_ref;

}

fn a(&self) -> &str {

&self.a

}

fn b(&self) -> &String {

unsafe {&*(self.b)}

}

}

Let's walk through this example since we'll be using it the rest of this chapter.

We have a self-referential struct Test. Test needs an init method to be

created which is strange but we'll need that to keep this example as short as

possible.

Test provides two methods to get a reference to the value of the fields

a and b. Since b is a reference to a we store it as a pointer since

the borrowing rules of Rust doesn't allow us to define this lifetime.

In our main method we first instantiate two instances of Test and print out

the value of the fields on test1. We get:

a: test1, b: test1

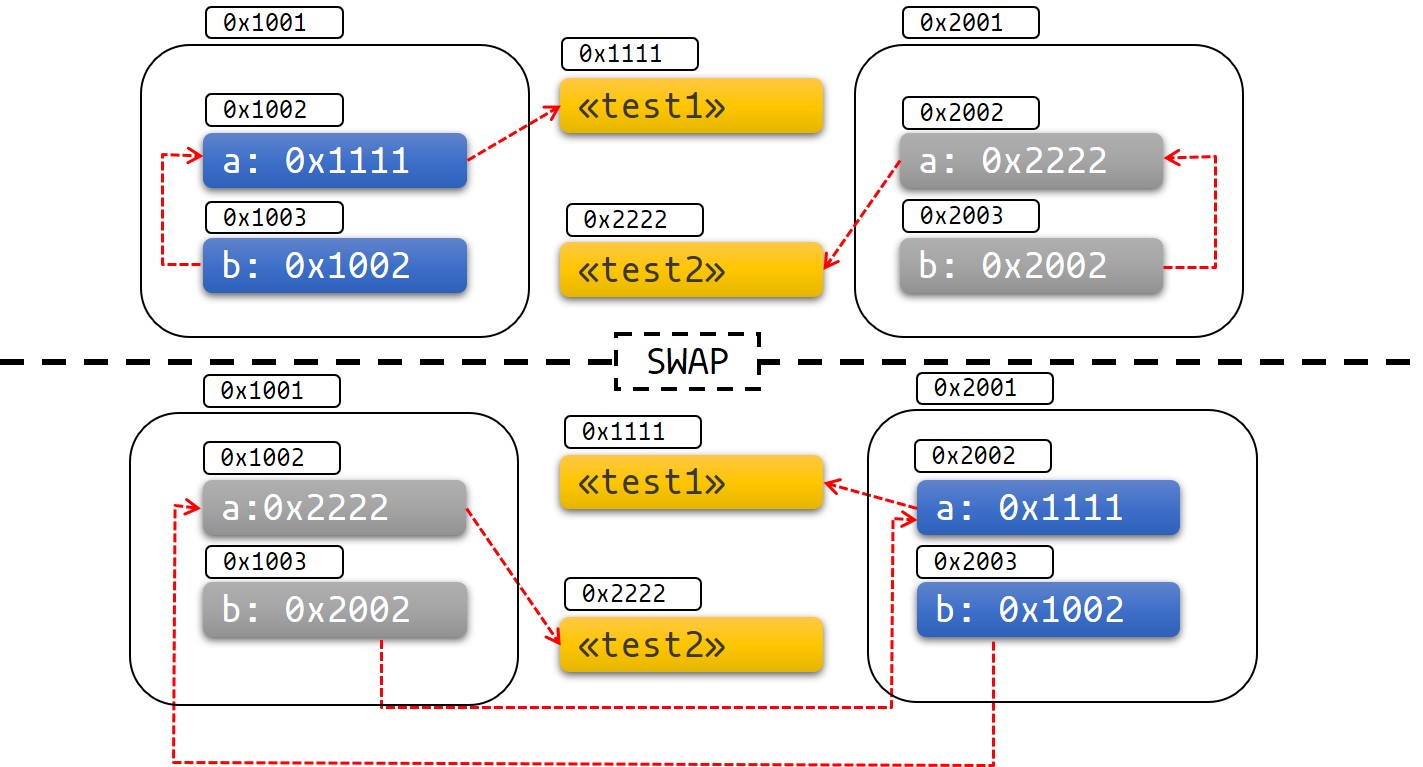

Next we swap the data stored at the memory location which test1 is pointing to

with the data stored at the memory location test2 is pointing to and vice a versa.

We should expect that printing the fields of test2 should display the same as

test1 (since the object we printed before the swap has moved there now).

a: test1, b: test2

The pointer to b still points to the old location. That location is now

occupied with the string "test2". This can be a bit hard to visualize so I made

a figure that i hope can help.

As you can see this results in unwanted behavior. It's easy to get this to segfault, show UB and fail in other spectacular ways as well.

If we change the example to using Pin instead:

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

let a = String::from(txt);

Test {

a,

b: std::ptr::null(),

// This makes our type `!Unpin`

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

}

fn init(&mut self) {

let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a;

self.b = self_ptr;

}

fn a<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a str {

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a String {

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

pub fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test1_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) };

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

let mut test2_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) };

println!(

"a: {}, b: {}",

Test::a(test1_pin.as_ref()),

Test::b(test1_pin.as_ref())

);

// Try to uncomment this and see what happens

// std::mem::swap(test1_pin.as_mut(), test2_pin.as_mut());

println!(

"a: {}, b: {}",

Test::a(test2_pin.as_ref()),

Test::b(test2_pin.as_ref())

);

}

Now, what we've done here is pinning a stack address. That will always be

unsafe if our type implements !Unpin (aka MustStay).

We use some tricks here, including requiring an init. If we want to fix that

and let users avoid unsafe we need to pin our data on the heap instead.

Stack pinning will always depend on the current stack frame we're in, so we can't create a self referential object in one stack frame and return it since any pointers we take to "self" is invalidated.

The next example solves some of our friction at the cost of a heap allocation.

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Pin<Box<Self>> {

let a = String::from(txt);

let t = Test {

a,

b: std::ptr::null(),

_marker: PhantomPinned,

};

let mut boxed = Box::pin(t);

let self_ptr: *const String = &boxed.as_ref().a;

unsafe { boxed.as_mut().get_unchecked_mut().b = self_ptr };

boxed

}

fn a<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a str {

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a String {

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

pub fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test1.as_ref().a(), test1.as_ref().b());

// Try to uncomment this and see what happens

// std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test2.as_ref().a(), test2.as_ref().b());

}

The fact that boxing (heap allocating) a value that implements !Unpin is safe

makes sense. Once the data is allocated on the heap it will have a stable address.

There is no need for us as users of the API to take special care and ensure that the self-referential pointer stays valid.

There are ways to safely give some guarantees on stack pinning as well, but right now you need to use a crate like pin_utils:pin_utils to do that.

Projection/structural pinning

In short, projection is a programming language term. mystruct.field1 is a

projection. Structural pinning is using Pin on fields. This has several

caveats and is not something you'll normally see so I refer to the documentation

for that.

Pin and Drop

The Pin guarantee exists from the moment the value is pinned until it's dropped.

In the Drop implementation you take a mutable reference to self, which means

extra care must be taken when implementing Drop for pinned types.

Putting it all together

This is exactly what we'll do when we implement our own Futures stay tuned,

we're soon finished.